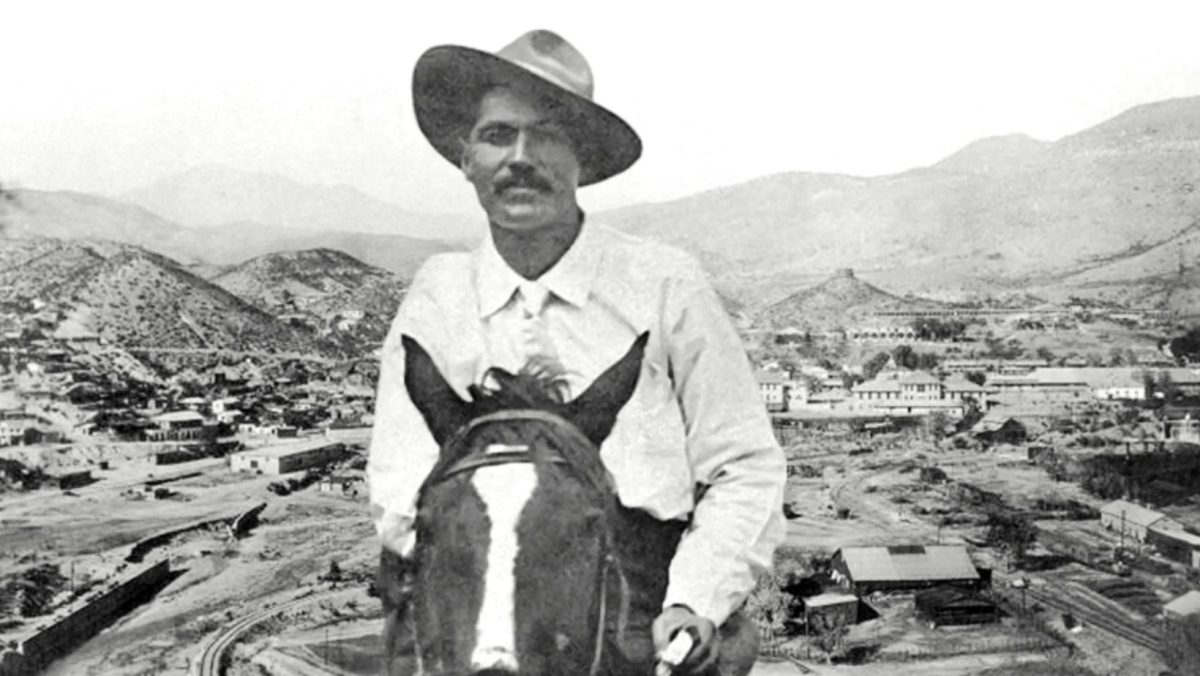

The Savior of Nacozari

8 de noviembre de 2023

By Thomas C. Romney

Seventy-five miles from Douglas, Arizona, in the state of Sonora, nestles deep in a canyon in the city of Nacozari, one of the important mining camps in northern Mexico. It was built by the Moctezuma Copper Company, a branch of the Phelps-Dodge Company, as a center for their extensive mining interests throughout a large area in northern Sonora. Here they built one of the finest concentrating plants in the world to process the ore from several mines, conveyed there by the company’s system of railroads. When I was there more than thirty years ago, there were about two thousand inhabitants, made up chiefly of Mexicans and Americans, most of whom were in the employ of the company. Like many others, I went there to retrieve a small fortune lost in mine speculations and found employment in the building line. The majority of the houses at Nacozari were company-built and company-owned, and to the credit of the company, be it said, they paid their employees well.

In 1907 I was acting foreman for the company in the construction of their buildings, and as such, was on my way from a row of tenement houses under construction to the planing mill when I observed a train of cars winding its way over the circuitous route leading up the steep acclivity east of town. There was nothing unusual about such an event, for trains were constantly going back and forth from the mines, except that in this instance, the train seemed to be on fire.

I watched it with interest and with considerable curiosity until the last car had passed over the summit of the hill, when almost immediately there occurred the most terrific explosion that I had ever witnessed. The force of the concussion was so violent that it seemed to me my head would be blown from my shoulders, and as if by instinct I found my hands locked over the top of my head to keep it from being blown into space. After the shock was over, I went at top speed to the summit of the hill to discover, if I might, what had happened. The sight I beheld beggar’s description and, like Banquo’s ghost, it haunts me still.

The first tragic scene in the picture was a dead man lying on his back with the warm blood from his body flowing down the hill in a small rivulet. Passing on, I observed that the warehouse which had stood by the side of the track had been so completely demolished that not one particle of evidence remained to confirm the fact that such a building had ever existed. Even the solid shelf of rock on which the building once stood had received a scar fully three feet deep. Off to the left three hundred yards from the track had stood a tenement house that had sheltered several families. To my astonishment, the structure had been blown to atoms. Not one stick of timber was in its original position. Several of its occupants had been blown into eternity, but worst of all, my eyes fell upon the forms and features of two women, a mother, and daughter, who had been gazing out of the window at the approaching train when the explosion occurred. The glass from the window was hurled with such terrific force into their eyes that they were literally torn from their sockets, and nothing was left but great gaping, hideous cavities, where once the eyes had been. And those sightless women could not die but were destined to live on in a world of total darkness, subjects of charity until a kind providence should see fit to end their sufferings.

I then looked about to ascertain the damage to the train and saw that the engine had been dismantled, and learned that the body of the engineer had been blown from the cab and was lying horribly mangled by the side of the track.

Anxious to learn the cause of the disaster, I interviewed a group of men standing nearby and received from them a detailed account of the accident, the essential features of which I now pass on to my readers.

The train had come from the mine loaded with ore and was to return laden with an assortment of merchandise for those employed at the mines. On one car was loaded six thousand pounds of giant powder taken from a great stone magazine situated at the foot of the hill, and in another car, several tons of baled hay had been placed. When all was in readiness, the engineer gave the signal, the engine began to puff, and the train started to climb the hill. When less than half the distance had been reached, the engineer cast a backward glance, and to his consternation, he saw the sparks from the engine had set aflame the bales of hay and that the burning hay, in turn, was being blown into the midst of the tons of powder contained in the open car immediately in the rear.

“Run for your lives!” shouted the youthful Mexican engineer to the train crew and a dozen passengers on their way to the mines. No second command was needed, and in a moment Jesús was left alone.

His Gethsemane had come. He, too, might escape, but what of the thousands in the town below? Should the powder explode at this point, the jar would be sufficient to set off the hundreds of tons in the magazine below, and then what? Not one of the thousands would live to tell the tale. Great beads of perspiration protruded from every pore, and with a heavy groan, he opened wide the throttle and the train sped on. Scarcely had the summit been reached when the powder exploded, but the courage of the engineer had saved the town.

Two years had passed. The sun was about to sink from view behind a serrated peak when a train of cars was seen coming down the steep declivity east of town. It was crowded with men, women, and children on their way from the mines. They had come to witness a solemn event, the unveiling of a monument to the memory of Jesús García, the youthful Mexican engineer. Multitudes had assembled—Mexicans and Americans; social differences were cast aside and all were blended into one great throng to pay homage at the shrine of the hero who died that they might live. Words of eulogy appropriate for the occasion were spoken and strains of soft-toned music floated out on the evening air in heart-breaking loveliness as only a well-trained and emotional Mexican orchestra can produce it. Then as a hush came over the assembled multitude, a veil was parted disclosing to view a polished granite shaft on whose base was inscribed a glowing tribute, the spirit of which was as follows: “To the memory of Jesús García, the courageous youthful engineer, the savior of Nacozari, who died that we might live. No greater love hath any man than this, that he should lay down his life for his friends.”

Years have passed since then, but those intervening years have not dimmed the memory of that courageous deed nor the sorrow of that widowed mother and orphaned sister as we tenderly placed in the casket the broken body of that heroic youth to whom honor and service were dearer than life.

Published on Powerful stories from the lives of Latter-day Saint men

Salt Lake City, Deseret Book Co., 1974

About the author:

Thomas Cottam Romney (1876-1962) was a leader of the Mormon colonies in Mexico in the early 20th century. He served as the Stake President (ecclesiastical leader) of the Mormon colonies in Mexico from 1907 to 1919. Thomas C. Romney played a pivotal role as a leader of the Mormon colonies in Mexico in the early 1900s during a tumultuous period, helping evacuate the colonists and documenting the history through his writing.

© All Rights Reserved