Pilares Mine at Nacozari Believed by Engineers to be Equal of Rio Tinto (1908)

24 de enero de 2023

By Chas A. Dinsmore

Sometimes one must of necessity write of the things as the light shines on them—so it is with the properties embraced in the holding of the Moctezuma Copper Company at Nacozari, Sonora, Mexico. After visiting the Pilares mine, the principal working, I feel to say, with the many others who have been accorded equal privileges, that it is the greatest mine I have ever seen. There are characteristics here, also, that makes reasonable the statement of several eminent mining engineers recently at the property—that they believe it to be the equal of the Rio Tinto in Spain.

Imagine, if you can, a pear 2,000 feet long, 100 feet wide at the stem, and 300 feet wide at the base, with a skin from 10 to 300 feet thick, and with two seeds in the core, one averaging over 75×175 feet, the other more than half so large. That is the Pilares mine—and all the skin and those two seeds are ore running 5 to 10 percent copper—and some of it runs away above it. They are now down some 500 feet in this property, the drill has gone another 400 feet—and they are in ore everywhere. They are handling the Guadalupe stope (the biggest seed) as well as the skin on the stope and pillar system—work out a stope 50 feet, then leave a 50-foot pillar of solid ore, and so on. When they take down the pillars, they will do so on the top-slicing system.

Not so many years ago, J. G. Alexander, a competent mining man, and prospector went “down into the heart of the Yaqui country” and after some time, he found and located what is now the Pilares mine. He did some work, and ran in a tunnel about 75 feet, but the showing didn’t justify the work, and he turned down the prospect and abandoned it. Later a short time, the Guggenheims got hold of it, and they worked out considerable ore in the “caliche” to the north of the deposit. But this ore body pinched down to a very doubtful proposition. Now it is said (and nobody knows whether it’s true), that the Guggenheims decided when they thought their Pilares mine was pinching out that they’d give the Phelps-Dodge people a chance to get rid of a big white elephant. So Mr. Douglas, pere, was seen about it, and he and his sons, James and Walter, went down to take a look at it. They knew something about the country as a general rule and they knew a lot about copper. Advising the purchase, the Douglases, of course, put it through, and the son, James S. was put in charge. That he has developed one of the greatest copper mines on the continent speaks in volumes of the sagacity and mining knowledge of this family of experts.

One reaches Nacozari through Douglas, Arizona, and by way of the Ferrocarril de Nacozari, a railway owned by the Phelps-Dodge interests, who also own the Moctezuma Copper Company, the Copper Queen mines at Bisbee, the Copper Queen smelter at Douglas, and other extensive properties throughout this section as well as the famous coal fields of the Dawson Mining Company at Dawson, N. M. This road takes one up and down through a winding valley, with towering peaks on every side, and fertile fields, all refreshing after hundreds of miles traveled over arid wastes to get here. The distance from Douglas is about 75 miles.

The town of Nacozari is owned by the mining company, and the manager James S. Douglas is really the monarch. He has studied this matter of town-making, too, as is evident by the success of his initial effort. Here are two saloons, one for the Mexican laborer and the other for the higher classes of all races. The first closes at 7 p. m., the latter at 9, and neither love, money nor friendship can induce any particle of the liquids to be dispensed at either place till 5 o’clock the next morning.

The company owns and conducts the hotel, first class in every way; owns the store, one of the largest wholesale and retail establishments in the southwest; owns the waterworks, electric light plant—in fact, everything but the people—and there are those who say they own a majority of these.

The country is very rugged. An abundance of timber is found everywhere, and there is water in abundance and of very good quality. The general formation is an andesite, with belts or dykes of rhyolite cutting through now and then, and sometimes little lime. The ore (copper) makes in the andesite. At times, small fissures cross the country and carry usually high silver values, tetrahedrite being the predominating metal in these. Sometimes gold in good quantity is associated. Sometimes, too, the copper runs very high, and now at one small property leasers are taking out quantities of almost solid red oxide running extremely high. The country is so stable that if one finds the conditions he well nigh knows what he will get, thus making exploitation less hazardous than common. The small properties being worked pay handsomely, as well as the big.

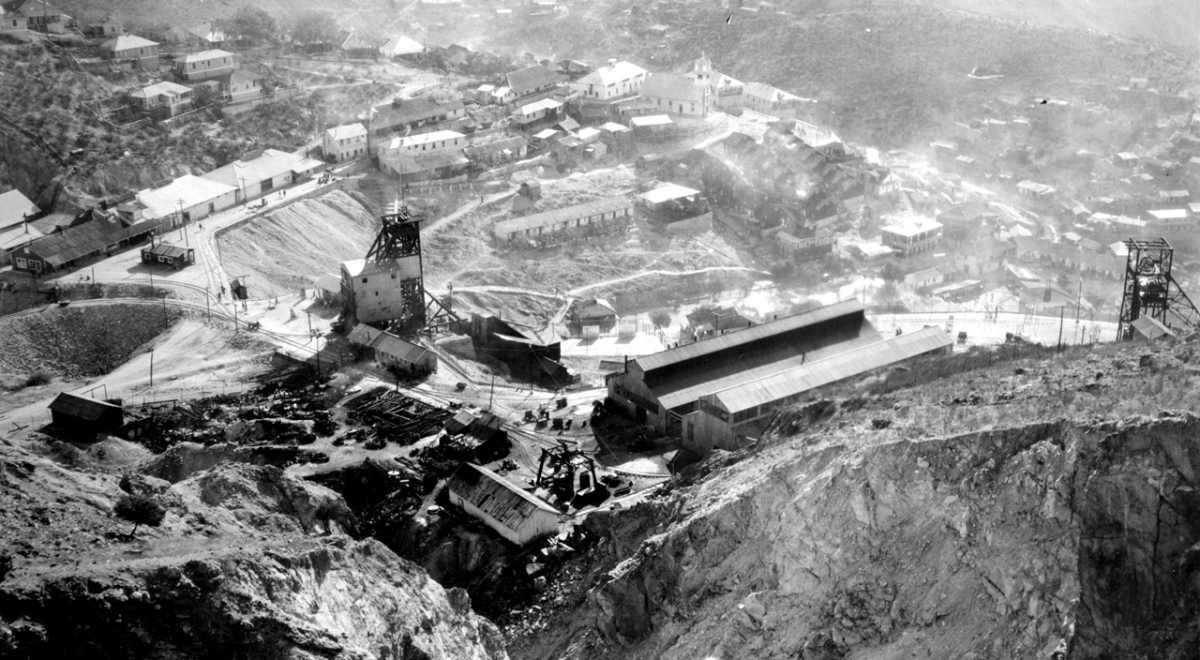

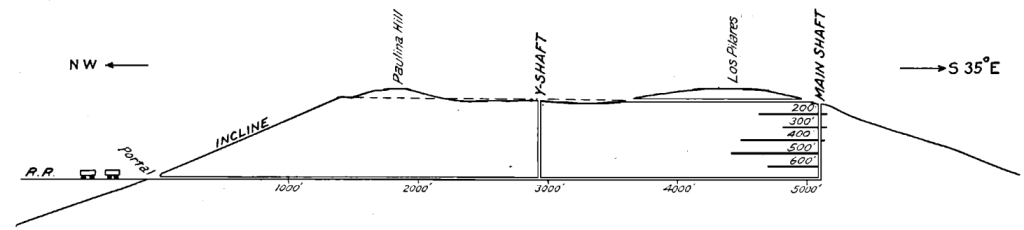

The narrow-gauge railway takes one from the town to the mine, a distance of about four miles. This mine is called the Pilares. The railway stops at the mouth of a 6,000-foot tunnel, which ends at the Pilares shaft. In about a third of the distance of the tunnel is the “Y” shaft. From the tunnel floor to the surface is about 500 feet in the Pilares shaft, and at the surface is the town of Pilares, where are the works of the mine and where the mine workers line. C. A. Smith is general mine foreman, William Knight, and W. B. Hicks underground foremen; E. M. Rabb and George Putman, civil engineers, and William McKenzie, timekeeper.

There is quite a town here, the Mexican miners living in excellent brick houses built by the company. The office building is ample, and the big store supplies all the wants from a check for their money to everything in clothing, food, or drink.

The surface showings here is in what is called by the Mexican miners “caliche,” meaning a very soft andesite dyke. This has a tendency to cave and surface water precolates through it to some extent, this being the only source of water in the mine.

The “slickensides” are noticeable in many places. This “caliche” is the hanging wall in some places, but on the south and west of the ore body is a well-defined andesite wall dipping slightly. The ore bodies on the inside of the pear—named the Guadalupe and the Don Juan stopes—are the same in character as those on the outer rim of the pear, but they are perfectly dry and, in fact, the dust in these stopes is sometimes very annoying. Between the inner and outer bodies, the material is barren.

The ore is found around the entire pear or horseshoe, the narrowest point carrying 15 feet of ore and up to 300 feet. There are two of these ore bodies around the pear, one carrying an average width of 40 feet and the other an average of more than 100 feet. The lowest stope is on the sixth level, 500 feet below the surface. The ground below has been prospected with diamond drills and the ore takes great depth, increasing in value with depth. The drilling showed that there were good ore bodies for at least 300 feet deeper than the present lowest in this property, but all the grades of sulfides are found, from chalcopyrite workings. No native copper is found up to glance, and occasionally some bornite.

They are mining about 2,500 tons a day, working 200 miners and 80 carmen, with 75 contractors on the faces. The work is done by contract, prices ranging from $7 to $11 per foot, according to the nature of the ground. Mr. Douglas states that there is no comparison between this method and the day’s labor, and 50 percent of the ordinary mucking and all tramming is done by contract. All miners work by contract and get so much for each foot of holes drilled.

There are two methods of stoping now in use here. One style they break ore continuously for 100 to 200 feet at a stretch, reaching the roof by standing on the broken ore and drawing off the surface. When this has been done to the limit of the strength of the walls, they draw off all the ore and fill from the surface, and then repeat the process. The other method is to take shortcuts, 10 to 15 feet high, draw out all the ore and fill to within a few feet of the roof, then making another cut and proceeding as before.

The country rock is andesite and the rhyolite comes in as a volcanic outflow. A large part of the rhyolite is brecciated. The ore is found both in the andesite and in the rhyolite breccia, but the andesite is the original source of the ore. It is expected that all found in the lower workings will be in andesite.

📓 Download:

Los Pilares Mine. Nacozari, Sonora, Mexico (1906)

By Samuel Franklin Emmons

Society of Economic Geologists

They find some high grade, which is shipped directly to the Copper Queen smelted at Douglas, owned by the same corporation. Just recently, they have opened up a new body of very rich sulfides in the “Y” shaft country, and when this is opened up it is expected they will be able to ship a fair tonnage from this. It is in this section particularly, that Mr. Douglas has decided on the 50-foot stope and 50-foot pillar system of mining, as well as in other portions in the skin of the pear.

A great advantage in this mine is that all ore is chuted from every level to the 700—the main traction level—and loaded direct into the cars as they go to the mill. No ore whatever is hoisted. Another economy is that no waste is hoisted, but it is left in the mine to fill stopes. No water is hoisted—it all runs out through the waterway in the traction tunnel. The timber costs aggregate but a few cents Mex., per ton of ore, mined, as the hardness of the ground makes timbering generally unnecessary.

The miners here are all Mexicans, and yet, they do fine work, the drill men being among the best in the world. All drilling is single-hand work.

They drive 5 to 8-foot holes, breaking 5 to 15 tons of material to a hole. It takes six hours, traveling four miles an hour, and with no stops, to go through this mine. One will, in making the trip for investigative purposes, take about twice as long, and in his journeyings, he will use up at least twelve candles. No portion of the mine is without tracks, and about 25 percent is equipped with electric lights.

The power is electrically transmitted from Nacozari main power station. At the Pilares plant, however, there is a reserve of many thousand cords of wood for use in case of necessity. There are two boilers here, and steam can be connected with the hoists and thus the work would progress where there a shutdown of the electric plant for any reason. A new compressor has just been installed for carrying air to those portions of the property needing it. It is expected that work of sinking at the “Y” shaft will be resumed in about another month and forwarded to the tenth level. Then it was proposed to drive a traction level on the 1,000 and do all hoistings between the tenth and seventh by means of an automatic skip. The skip station has been cut out and all preparations are made for this new work and the shaft is ready for sinking operations, and they are now only waiting for the close of the rainy season. There is a winze 40 feet below the 700 and 8 to 14 percent ore.

An extremely conservative estimate places the ore in sight as sufficient for five years continuous work at 2,000 tons a day. But 60 percent of the ground above the seventh level has been explored. The figures are of the or is sight, and not that in a way developed by the diamond drill nor guesswork as to what may be in the 40 percent of undeveloped territory mentioned. There is absolutely no indication of anything but bigger bodies the deeper they go, and this gives the future of the Pilares a wonder look.

The company expects within a very short time to run a 1,000-foot tunnel to crosscut and tap a very likely prospect on the southwest side of the mine and outside of the horseshoe. This is called the San Juan property. An 80-foot shaft developed excellent ore and this will be deepened and the shaft and crosscut tunnel will connect at considerable depth.

It costs about $3, Mexican money, to mine and land a ton of ore on the cars. I asked Mr. Douglas his idea on stoping 50 feet and leaving a 50-foot pillar of ore, and he said: “We use the 50-pillar because the ‘caliche’ runs across the pillars and we believe that less than 50 feet would not hold the country long enough to get the ore out. Then we shall fill the stopes after the ore has been taken out, and we shall get the pillars by top slicing.”

—

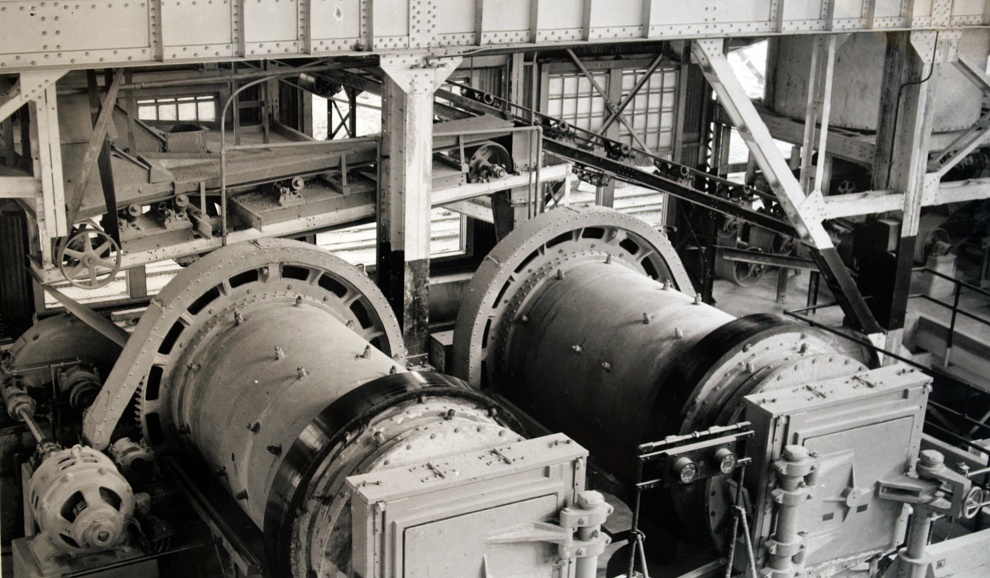

It is very possible that the concentrator at Nacozari, where the ores of the Pilares mines not rich enough for shipping are milled, is one of the most efficient in the country. It handles at the time I was there 800 tons a day, working with but half of the installation, when both units are in complete operation, the plan will easily handle 2,000 tons daily. The concentrator was built under Mr. H. Kenyon Burch, the chief engineer in charge of construction and mill superintendent. Mr. Burch’s life work has been the improvement of his work and the increase of efficiency of whatever plan he is connected with. Millmen who see the Nacozari plant become enthusiastic. The foundations, buildings, settling tanks are of cement, and indeed, wherever possible, it is all of this material, over $175,000 (gold) worth of it having been used in the completion of the milling and electric generating plant. Where in the old concentrator, it required fourteen men, Mr. Burch triples the amount of ore rushed and does it all with two men. The success of the new plant depends entirely on the attention to details and the doing away with much expense in labor, etc.

When I visited the plant a few days ago, but half the plant was in operation, and machinists, carpenters, etc., were busy in one end of the building installing the second unit, while in the first unit, they were “combining out the mazuma” at the ratio of one ton out of five.

The machinery in this plant consists of:

Two ore feeders at bin and crusher plant.

Two Grizzlis, 2 1/2 inch space between bars.

One No. 8 gyrator crusher.

One belt conveyor, 36 inches wide, 46 feet long, running 400 feet a minute.

Two 4×10 manganese-covered steel trommels 1 3/4 inch perforations.

Four No. 5 shorthead gyrator crushers.

One 24-inch belt conveyor, 332 feet long, running 300 feet per minute.

One 24-inch belt conveyor, 90 feet centers, 300 feet per minute.

One 18-inch belt conveyor, 205 feet centers, 250 feet per minute.

One 18-inch belt conveyor, 152 feet centers, 250 feet per minute.

One 18-inch belt conveyor, 89 feet centers, 250 feet per minute.

One same as above.

Four trommels, 42 inches in diameter, 6 feet long, 18 mm.

Four same as above, 11 mm.

Six same as above, 7 feet long, 7 mm.

Six same as above, 2 mm.

Fifty-six Wilfley tables.

Eight single-compartment bull jigs.

Eight single two-compartment coarse jigs.

Eight single two-compartment intermediate fine jigs.

Sixteen duplex callow screens.

Ten dewatering tables.

Ten Chilean mills.

Eight elevators in pairs.

Twelve feed distributors, for Wilfleys.

Seventy-two vanners.

Six sets 42×16 rolls.

Six dewatering feeders for rolls.

Two portable ore feeders from storage bins.

Eight feeders for Chilean mills.

Five 12×14 triplex pumps.

Two 4-inch centrifugal pumps.

Two 3-inch centrifugal pumps.

Two 10×12 table plunger pumps.

Three 75-hp. induction motors.

Four 150-hp. induction motors.

Four 5-hp induction motors.

Six 10-hp. induction motors.

Two 40-hp. induction motors.

Two 30-hp. induction motors.

Six 20-hp. induction motors.

Four 20-hp- induction motors.

Forty-eight 12×12 reinforced concrete settling tanks for reclaiming water from tailings.

Twenty elliptical-shaped reinforced concrete concentrate bins, 10x14x18 feet high.

Forty 12×12 reinforced concrete settling tanks, used as pulp thickeners for vanner feed.

The plant is notable of: Efficiency, equipment, neatness of design. The new features include: All the floors, including on and above ground, are of concrete. There isn’t a wooden floor in the building.

Elevator hostings are of reinforced concrete. Vanner baths are of reinforced concrete. Feed distributing machinery for Wilfley tables set in reinforced concrete. Feet distributing machinery for Wilfley tables set in reinforced concrete. Dewatering tables of jig tailings. Jigs, all of special design and cast iron throughout. Portable ore feeders under storage bins. Each feeder will accommodate nine different chutes.

Man elevator. From the Chilean mill floor to top of the plant, all concentrates and tailings are carried from mill through tunnels and trenches underneath mill floors.

Lighting—The mill is “always light as day.” There are innumerable windows for daytime and myriads of electric bulbs at night give the great structure a brilliant appearance. At no moment is there any hesitance about anything because of lack of light.

In fact, throughout the handsome plant, the mastermind is evident, and it is due to the extensive general knowledge of mining and the allied sciences of General Manager Douglas and the ability as a designer and constructor of Mr. Burch that so model a plant is operating down in the heart of the Yaqui country, many miles from what most would call “civilization.” There is reason for everyone to be proud of such an installation because many features are startling in the uniqueness and in the reaching out from the beaten pathway of concentrators, and the whole thing teaches boldly the enterprise and progress of the American of today.

The use of electricity is reserved to throughout the works of this company. It is generated in a great central powerhouse just back of the town of Nacozari. The boiler room is of corrugated iron, the turbine room of reinforced concrete, and the smokestack, fifteen feet in diameter and 184 feet high, is of reinforced concrete. Coal or wood is used as occasion requires, but the former mostly.

There are three 1,000-kilowat Curtis turbine generators, direct connected, generating at 6,660 volts. There are Alburger surface condensers and dry condenser pumps. The circular pump for the condenser is a Connersville. The main exciter set is a motor-generating set. An auxiliary steam turbine generator set of 50 kw. is used in starting. Four Sterling boilers of 435 hp. each are equipped with Foster super-heaters and Green fuel economizers.

There are three feed pumps and one steam pump. Two variable speed induction motor-drive feed pumps. There are two Worthington duplex pumps in the oil system. The switchboard is equipped with General Electric company’s instruments.

There is a 4-point relay Terrel regulator, which maintains a constant voltage on the generator. A total curve-drawing watt meter which records the total load at the station. There are seven panels on the switchboard as follows: One to the new mill; one to the Pilares mine; one to the pump supplying the city with water; one to the shops on opposite side of the river; one to the ice plant and for the city lights; a station feeder; one spare. There are all equipped with oil switchers, remote control, and watt meters for each circuit. There is a frequency meter and a synchronizing instrument.

Power is transmitted about six miles to the mine. At the mine they operate by electricity four electric locomotives; one 200-hp. electric air compressor for furnishing air to the mine, and the hoists are electrically operated. At the “Y” shaft there is a six-phase rotary converter, which takes the alternating current from the main powerhouse and transforms it to a direct current to be used locally.

W. E. Washburn is the superintendent of the powerhouse.

Published on Bisbee Daily Review

Bisbee, Arizona, September 13, 1908

Cover Photo: Pilares de Nacozari (ca. 1923) | Phelps Dodge Collection

About the author:

Chas A. Dinsmore was an editor and mining journalist active in Arizona in the early 1900s, working on publications like the Duncan Arizonian that covered local news as well as the booming mining industry across the Arizona/Mexico border region during that era. The sources highlight his role in the pioneering journalism landscape of early 20th-century Arizona.

© All Rights Reserved