Jesús García, A Hero Forged by Tragedy

1 de diciembre de 2022

By Frank Aley

History has recorded many instances of absolute sacrifice of one’s life for others, and this should have a place in the splendid category. The American who, when the frail craft on which he was serving was penned in by a British man of war, managed to steal stealthily aboard the English vessel and put a match to her magazine, will be remembered in history though his name cannot be identified.

Arnold Winklereid, as he gathers a half score of Austrian lances in his breast to form a gap that soldiers might pass over this dead body and take advantage of the beach, will be remembered. A hundred other heroes will be remembered, and it is but just that Jesús García, who gave his life to save that of a hundred others, should be remembered.

His Early Days

When 14 years of age, in the course of the construction of the Pilares “Highline” the narrow-gauge railroad over which streams the product of the great Pilares to Nacozari. Jesús García applied to W. L. York for employment, explaining that Danforth, by whom he had formerly been employed had insisted that he should work in a menial and humiliating capacity.

Admiring the boy’s sense of honor, York gave him employment as a water boy. Even alive and devoted to his duty, García gathered promotion. He was hired by York in this first instance at a point within ten feet of where his mangled body was afterward tenderly raised and carried to its resting place.

He was next given a shovel, then placed with the section gang. His devotion to duty was so pronounced and his sense of honor so evident, that he was made a brakeman, and from that, he rose to fireman, and from that became a locomotive engineer, which leads up to a recital of the actual facts concerning this terrible incident. The Pilares Highline is a narrow gauge, running from the concentrator in Nacozari to the Pilares de Nacozari mine, a distance of six miles.

At the time the tragedy occurred, the old concentrator was in commission. The railroad is a three percent grade going up from the concentrator, and a car released before it reaches the divided and passes over would inevitably roll back into the reduction plant.

On the 7th day of November 1907, it devolved on García in the usual course of his duty to pull the ore train from the Nacozari concentrator to the mine.

It occurs that the American conductor was indisposed and was off duty that day, and that particular capacity was not represented. One hundred and sixty boxes of giant powder were to be transferred that day from the magazine at Nacozari to the mine on this train. It was the usual and proper practice, of course, to swing the powder cars to the rear. This day there were six cars of merchandise, and the powder filled two cars. These cars were open and unprotected as ore cars always are.

García’s Only Mistake

In switching, García made a mistake, for which he subsequently heroically atoned with his life. Instead of switching the powder cars to the rear, they were coupled up next to the engine. This was a fatal mistake, but he had not had training in the capacity of a conductor; he was simply an engineer, and a young at that.

As he started up the first leg of the Y, the wind was such that it blew the sparks away from the train, but when he stretched out on the next leg, the wind was facing him and blew the sparks back on the cars. Being a three and-one-half percent grade, the engine labors heavily and your contributor can testify to the severity of the cinder storm which falls on the first two cars.

The current story that a bale of hay was on one of the cars of powder is pure fiction. The train had not proceeded more than about six hundred feet when it was discovered that one of the powder cars was on fire.

Another hero of the incident which escaped and who deserves the greatest measure of credit is Francisco Rendón, who, after the fire started, attempted to pull the burning box of powder away, but was unable to do so for the reason that it was jammed, being expanded by the heat and wedged in. One could not place too much credit on this man, though his heroic efforts were unavailing. Rendón was a brakeman, but on this occasion, he was not working and was a passenger to the mine.

Refused to Jump

When the fire was discovered, the fireman pleaded with García to jump. “No,” said García. “You get off and save yourself. I will stay with her. If I quit her, she will slip, run back and blow up the whole works. It is better for one man to lose his life than a hundred.”

A finer example of human devotion cannot be conceived. In the terrible strain of the moment, García did not remember that the catastrophe might occur alongside the section house which they were approaching.

As fate would have it, just as they were whirling by the house the frightful concussion came. “Tío” York, who was eating at a restaurant in Nacozari, a mile away, states that it shook the dishes off the table. Mr. Gaughran, who was at the Nacozari Consolidated then miles away, states he heard it distinctly. The effect, as might be presumed, was terrific.

The section house was blown to kindling wood and several women and children torn to pieces; the different members of human bodies being scattered over a radius of several hundred feet. Twelve people were killed, including García, and one profoundly pathetic detail appears in the fact the two young girls lost their eyes and are pensioned now by the Moctezuma Copper Company, which was distinguished for its sympathy and generosity all the way through, and the hands of Mr. James S. Douglas, the general manager.

The explosion developed many freaks from the standpoint of science; objects comparatively nearby being immune, and others at a great distance being destroyed.

Scene Slaughter Pen

The section house suggested a slaughter pen after the mighty roar subsided and the debris had to be cleared away in order to recover the dismembered bodies of the dead. The engine, strange as it may appear, was still on the track, and the body of Jesús García was found within 20 feet of it, burned and crushed almost beyond recognition. He was carried to Nacozari and interred in the old cemetery just below Placeritos, the local name for that city.

James S. Douglas, on learning of the said affair, ordered a special train and flew from the city of Douglas to the city of Nacozari. Both personally, and on behalf of his company, he advanced every species of assistance and relief, which means could command.

He personally attended the funeral of young García and demonstrated his profound sympathy and regret on that occasion. The company, along with the city government, subsequently raised the necessary sum to erect the monument which was unveiled on November 7th, 1909.

The event impressed not only the local community, and the Mexican population profoundly, but the American colony joined in the universal feeling of sympathy and regret and contributed in every possible manner for the alleviation of the injured and proper disposition of the dead bodies of those who fell.

A veteran engineer would never have coupled up to open cars loaded with dynamite. Had the conductor been there, he would not have permitted it. Again, old engineers who have grown gray in the service on standard railroads, state that he could have saved his splendid life by throwing her open and jumping, and even if the train threatened to roll back, it could easily have been derailed.

It is a profound pity that his noble young man could not have had the necessary experience to have availed himself of the facts and saved his life. As it was heroism made up his inexperience and his noble intentions, carried out as they were entitled his name to be emblazoned on the escutcheon of immortality and engraved on the memory of everyone who honors him died for others, even as he who made the same sacrifice on Calvary.

Another Pathetic Side

Another pathetic side, reflecting at once human heart throbs and human philanthropy, is the fact that every month the old mother receives her son’s check, and every month, while grateful for the indispensable source of existence, her heart is sorely wrung.

Every month, she says to herself, “Though gone, my boy is still supporting me, if not by his experience and foresight, yet by his heroism, he is still caring for my physical needs.” And through that pious faith instilled by the devoted fathers of her chosen church, she is comforted with the conviction that the spirit of her boy still hovers about her, and meeting life’s disappointments with a courage born of that faith, she patiently awaits the hour when she shall join him in a realm unknown to alarms, tragedy, disappointment or separation.

This sad affair offers a powerful object lesson with more than one completion to it. We can afford to study and ponder on it. Yet may the diverse conclusions be what they shall, the fact remains that a cleaner, nobler, and more splendid hero never lived than this little obscure Mexican boy, Jesús García.

“His life was gentle and the elements so mixed in him, that nature might stand up and say to all the world: THIS WAS A MAN.”

Published on The Bisbee Daily Review

Bisbee, Arizona, November 6, 1909

Original Title: Will Honor Dead Hero at Nacozari

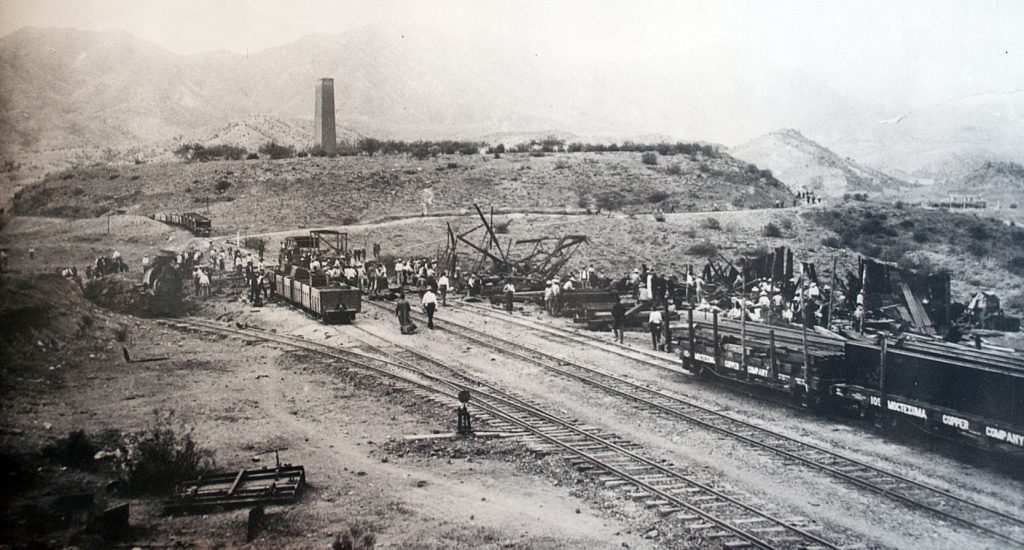

Cover Photo: Crew of Engine 2 (ca. 1906) | Arizona Historical Society

About the author:

Frank “Mescal” Aley (1860-1910) was an Arizona pioneer, lawyer, newspaperman, and renowned mining writer in the early 20th century. He was also a mineralogist, humorist, and writer who used the pen name “Mescal”. Aley worked as a journalist and mining reporter for various newspapers in Arizona, including the Bisbee Daily Review, Tombstone American, and Douglas newspapers. He covered and reported extensively on the booming mining camps and districts in Arizona and Sonora, Mexico, gaining expertise in the mining industry.

© All Rights Reserved

🎧 Listen to the Acts of Impact podcast episode (by Alex Grohls) dedicated to Jesús García on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.