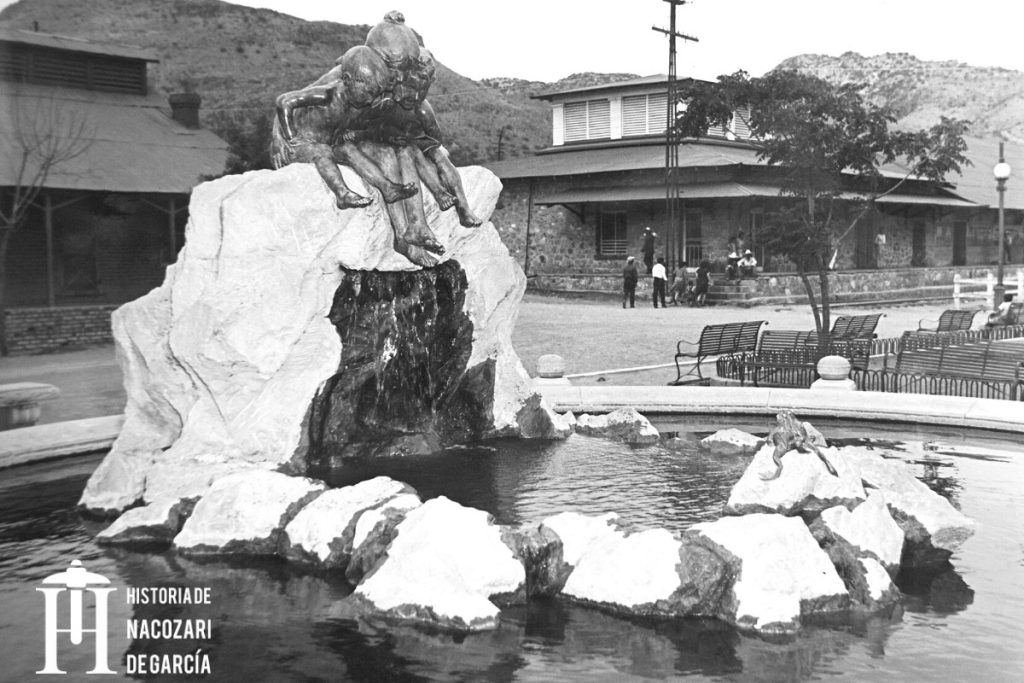

Douglas Memorial Fountain at Nacozari, Sonora, Mexico

26 de noviembre de 2022

By Leslie G. Cauldwell (1921)

In 1918 at a picture show held by a group of American artists in Paris, I exhibited some pastel studies of French soldier types. My pictures attracted the attention of Mr. James S. Douglas, and later when we met at Red Cross Workers, I asked him up to my studio. On my staircase walls were a number of watercolor drawings made in connection with my profession as architect-decorator, and these drawings led to the following conversation:

Mr. Douglas told me that he had but lately lost his father, Dr. Douglas and that his brother and sisters wished to erect a memorial to their father’s memory in the little mining town of Nacozari in Mexico, which Dr. Douglas especially liked. Then Mr. Douglas fixed me with a twinkle in his eye and asked me whether I would consider the idea of going out to Douglas, Arizona, and from there into Mexico to put up this memorial, which was to be a copy of a fountain he had seen in Dijon, France.

At first the thought of leaving my delightful studio in Paris and going out to what I imagined to be “the wild and wooly West” nearly took my breath away. Yet, at the same time, the idea appealed to me as very interesting and as fulfilling a long-cherished desire to visit that great southwestern country of my native land.

The difficulty was that Mr. Douglas did not know by whom the bronze group was made. He had seen it in Dijon—that was all. But, as luck would have it, a young French lieutenant, for whom I was godfather during the war, was going to transfer to an African regiment at Casablanca and asked me to dine with him on the evening of this departure and meet his aunt and his very pretty fiancée. I accepted! One would do so for less.

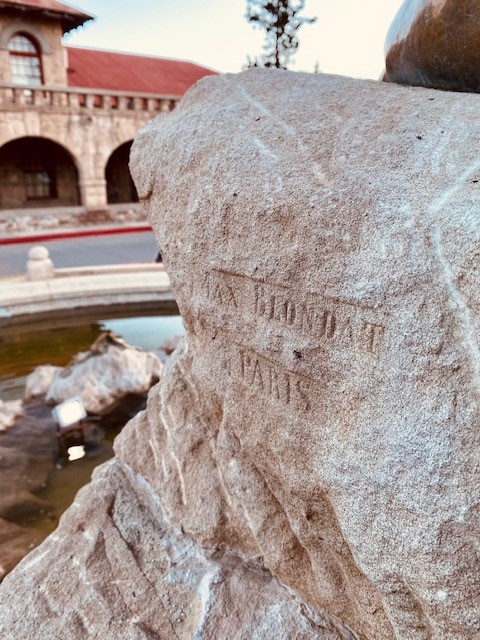

The fiancée was indeed pretty, and—she came from Dijon. It did not take long to find out that the author of the bronze group in Dijon was Max Blondat, the great French sculptor. It was an easy matter then to get in touch with Max Blondat, and after an exchange of letters, I was commissioned by Mr. Douglas to order the group to be cast in bronze by the cire-perdue process at once the most artistic and the most costly.

The cire-perdue, or “lost wax” process was that so much employed by the great Renaissance sculptor Benvenuto Cellini in the sixteenth century. In it, the original wax model made by the sculptor is covered by successive layers of clay, and when sufficient thickness is obtained, this mould, into which copper pipes have been cleverly introduced, is put in the kiln, at such and such temperature, and all the wax runs out, leaving a perfect mould. Other tubes previously placed are then used to fill the mould thus emptied with molten bronze. Thus you have the direct touch of the sculptor in the bronze—which quality is often lost by other and more commercial processes.

It was part of my business to go to the foundry of M. Valsuani in the far-away Montrouge quarter of Paris and make arrangements for this casting. But in the meantime, I had received a blueprint showing the plaza of Nacozari. “Here was the Gracía monument; here the bandstand, and this other square was where the fountain would be placed.”

The ground was apparently absolutely level. To my Paris ideas of the West, there was nothing unusual in this, but I realized that the little stone basin which formed the fountain in Dijon would be lost in this public square like a postage stamp on a tablecloth. So I wrote to Mr. Douglas and suggested a new plan for the basing, and in Mr. Blondat’s studio had made a maquette or plaster model to scale after the sketch I had modeled in clay, and shipped the maquette off to Arizona.

In my plan, the group of children, as at Dijon, are seated on a high rock from which the fountain gushed out. The frogs at which the children are looking, instead of being placed on the curbing of the basin, are on a small rock emerging from the little pool out of which the water falls into a large circular basing about 21 ft. in diameter.

This circular basing is surrounded by an 8-ft. stone walk which is elevated above the level of the park about 3 ft. This walk is reached by three flights of stone steps, the number three being at the request of Mr. Blondat. The stone steps are connected by a circular stone curving which encloses a bad of rich soil slating to the upper level of the steps. In this band will be planted hardy plants to form a circle of green around the fountain and reduce the seeming importance of the stonework. It is this model that I have been putting up in Nacozari.

On my arrival at Nacozari the night of November 24th, 1920, there being no one to meet me at the station, I wondered off in what seemed the right direction, and almost immediately came upon a high circular fortress which looked for all the world like the large Bosch pill-boxes I had seen in the Argonne.

My Parisian stone carver, Monsieur Ratti, was with me; and I said in French, “My God, that is the fountain!”

“Never!” he replied. “It is at least five feet high.”

But it was the cement foundation of the fountain, only the ground instead of being perfectly level, as shown in the blueprint I had in Paris, slanted about two feet from back to front.

That night at the hotel I tossed and tossed, always coming up against the fortress fountain, until I found the solution of the problem and slept. The next morning I met Mr. Hamliton and Mr. Irwin and they confessed that the aspect of that cement wall had demoralized them and that they had stopped all work until I arrived. I showed them a sketch I had made to obviate the difficulty by raising the level of the park and having steps leading to the street, and with their approval, I wrote at once to Mr. Douglas on the subject. This change of level made it necessary to alter the entire layout of the park, and so I made a new plan which Mr. Douglas accepted, thus making a setting for the fountain worthy of the bronze by Max Blondat.

This bronze, as I mentioned, represents three little girls sitting on a ledge of rock overhanging a cascade and pool of water. They are looking down at three frogs who have snuggled together on a stone and are gazing up at the children. The oldest child, about ten years old, is frankly amused; the second, about six, is smiling too, but the little tot, not yet three, is not quite sure about the situation.

Max Blondat calls his group Jeunesse— “Youth.”

I call it the “Fountain of Smiles”, for no one can stop and look at this chef d’oeuvre without a sunny smile creeping from eyes to mouth. Old Mexican men and women, young girls and youths, mothers, fathers, and school children, all feel the spring of guileless happiness the group imparts.

The material difficulties in building the fountain were removed as far as possible by Mr. Hamilton and Mr. Irwing, The limestone had been cut to my plan by the John A. Rowe Cut Stone Company of Bedford, Indiana, and shipped to Nacozari. But there were of course stones to be prepared on the spot, and it was, as we say in Arizona, “some job”, to educate a miner into being a good stone cutter who respected the edges of mouldings and finish the surface; but even that had been accomplished.

The last wonder of all is that we are going to be able to cast in Nacozari, after the details mare from my sketch, the copper lamp posts to light up the fountain and park.

Near the top of each are four jolly little dolphins which wriggle downward with their tails in the air. They carry in their mouths bronze rings, which are mobile and strung from there, from post to post, will be hung garlands of tiny lamps on the nights of fiestas, so that through the branches of the pepper trees they will look as if the multitude of fairy fire-files had come to dance a saraband about Max Blondat’s group and invite the three bronze children to step down and join the fun.

Written for Engineering and Mining Journal

New York, June 4, 1921. Vol. 111, Number 23

Cover Photo: Phelps Dodge Collection

About the author:

Leslie G. Cauldwell (1861-1941) was an American artist known for his work in portraiture, figure painting, and landscapes. He was primarily active and lived in New York. Cauldwell passed away on April 9, 1941, in Paris at the age of 79.

© All Rights Reserved